Software: The End of the Starchitect?

Conquering the world through tools instead of Skyscrapers

Intro

The architectural profession has long celebrated the "Starchitect"—a figure whose influence was measured by the ability to alter city skylines with towering skyscrapers. These structures, emblematic of modernism and postmodernism, stood as testaments to personal creativity and innovation. Contributing to significant city skylines like Manhattan’s could take you to the highest levels in the profession.

Yet, as we venture deeper into the digital age, the means of achieving architectural influence undergo a profound transformation. Are we witnessing the end of the starchitect era, supplanted by the rise of software as the new domain of architectural mastery?

This means that substantial industry impacts can happen differently: through software. By making tools people use to design buildings, you’re, in a way, impacting all their practices and their work.

The Impact of Software in Architecture

Software has irrevocably changed the architectural landscape over the past few decades. Starting with Computer-Aided Drafting (CAD), we went from physical to digital drafting, directly emulating what we used to do on a drawing board on a computer. Then we went several steps further with BIM, fully digitalizing the design process using 3D models paired with element metadata (parameters, meaning key-value pairs of information associated with geometrical elements), effectively making a hybrid of geometry and database, from where we can go backward to 2D (getting bidimensional plans like floor plans or section cuts quite fast), or to 4D and beyond (planning, material takeoffs/costs, etc.), constituting a digital twin of the physical building.

These tools have revolutionized the design process, enabling architects to draft, iterate, and visualize projects with unprecedented precision and efficiency. Of course, this is not without several traps and issues.

Now, we’re at a point where opportunities and barriers of entry are much lower than before to create apps on top of CAD and BIM-based workflows for multiple —almost unlimited?— applications in the AEC industry.

This is where the influence becomes exponential and gains scale. I’ve seen firsthand with projects at e-verse how we could reduce more than 80% of time spent on designing solar energy parks of 100k+ solar panels, automatically route thousands of electrical cables in a building design through the most optimal paths, generate dozens of variations for a building design automatically based on input parameters, translate a BIM model to the field with auto-alignment using AR, automatically reuse already in-stock structural elements in new designs at a 2k+ people engineering firm, or fabricate framing pieces directly from a BIM model, as some examples.

The Evolution of Architectural Influence

Architects became household names through their unique contributions to the global skyline, from Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater to Zaha Hadid's Heydar Aliyev Center. However, the digital revolution introduces a paradigm shift, directing the spotlight from concrete to code. The influence expands beyond the drafting table, embedding itself in the software that underpins the creation of modern architecture.

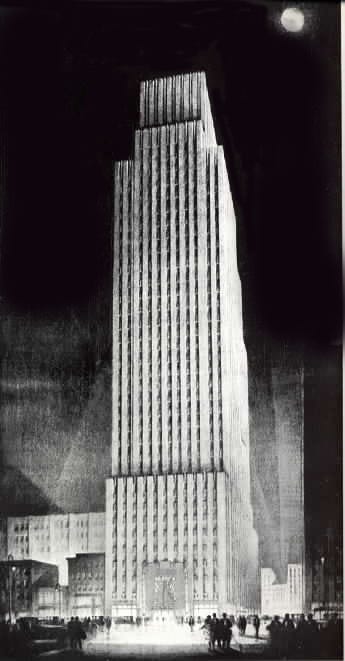

This mechanic is similar to Hugh Ferriss and his hand-made renderings of New York buildings in the 20s — he wasn’t only providing a means of design communication, he was influencing the designs themselves through his tool: the sketch. He was providing a framework through which buildings were incubated and finally born.

Ferriss' most important contribution to the theory of Manhattan is exactly the creation of an illuminated night inside a cosmic container, the murky Ferrissian Void: a pitch black architectural womb that gives birth to the consecutive stages of the Skyscraper in a sequence of sometimes overlapping pregnancies, and that promises to generate ever-new ones.

Each of Ferriss' drawings records a moment of that never-ending gestation. The promiscuity of the Ferrissian womb blurs the issue of paternity.

The womb absorbs multiple impregnation by any number of alien and foreign influences-Expressionism, Futurism, Constructivism, Surrealism, even Functionalism-all are effortlessly accommodated in the expanding receptacle of Ferriss' vision.

Manhattanism is conceived in Ferriss' womb.

— Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York

Consider an architect who shifted focus from designing buildings to developing software and tools, recognizing the potential to impact the industry (or at least their firm) on a larger scale. Now used by thousands worldwide, their tools allow for more sustainable, efficient, and cost-effective building designs.

While skyscrapers once defined an architect's legacy, software enables a subtler yet more pervasive form of influence. Like Ferriss’s drawings, architects who develop innovative software tools provide a framework for (hopefully) better design, shaping the built environment and thus impacting how communities live, work, and interact on a larger scale.

The Traps of BIM

The shift towards digital tools is not without its challenges. We can argue that an overreliance on software can detach architects from the tangible aspects of their work, potentially stifling creativity. Also, the accessibility of advanced tools raises concerns about the homogenization of design and the potential loss of cultural and contextual sensitivity in architecture once again — does modernism ring any bells?

But, more tangible than that is the fact that most architectural and engineering firms are spending thousands of hours building complex, coordinated BIM models, to then go back to printing sheets of 2D plans that eventually are the final source of truth that’s used to build, with tremendous information loss in the process.

This leaves us with a question: does the time saved in the design process justify the extra hours used to build detailed BIM models? I want to believe the answer is yes. But I also think it’s a matter of time before the BIM model is used directly in the field, with no back-and-forth translations to 2D at least, if we want BIM workflows to not only make sense but to become an absolute no-brainer if analyzed in terms of ROI.

The “final” shape of BIM will be determined not only by using BIM-based tools and workflows but also by adapting the way we communicate design intent and how we collaborate as teams to produce those designs, potentially improving or redesigning the systems we use to generate them.

“Organizations which design systems are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.”

—Melvin E. Conway, How Do Committees Invent?

Conway’s Law already sums it up if we apply his concept in the context of the AEC industry.

Reimagining the Starchitect

The architectural influence is no longer confined to the physical realm. As software becomes central to the design process, it offers a new platform for architects to express their creativity, solve complex problems, and impact the built environment. In this digital age, perhaps the accurate measure of an architect's legacy will be the tools they develop and the innovations they inspire, marking a shift from conquering the world through skyscrapers to shaping it through innovation — from concrete to code.